Is China’s Deflation a Bug or a Feature?

“The Chinese nation is the most patient in the world; it thinks of centuries as other nations think of decades.”

– Betrand Russell, 1922

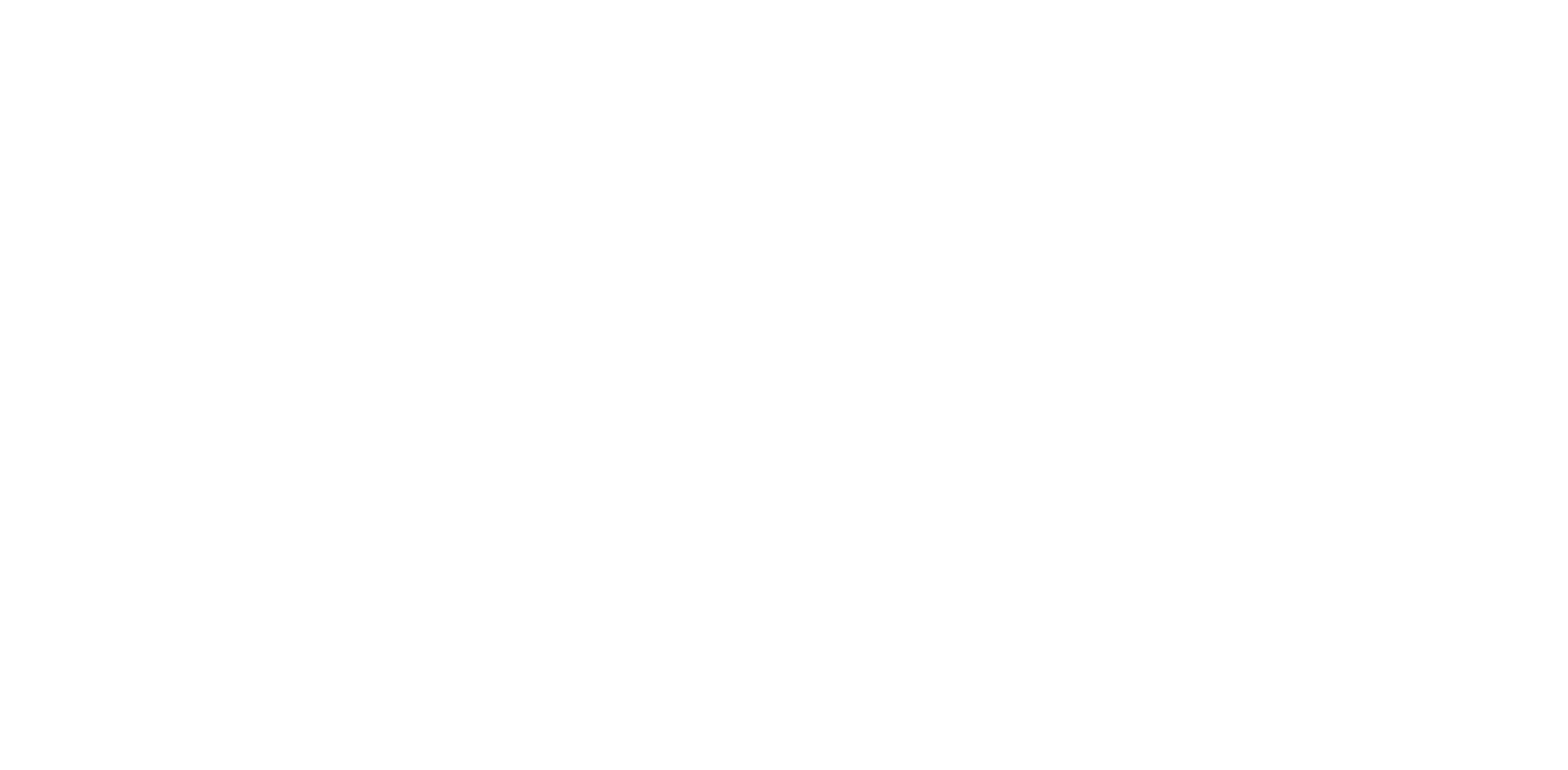

After a post-Covid demand surge pushed Chinese producer prices higher, in October 2022 the Chinese Producer Price Index (PPI) – or the price producers receive for what they produce—declined YoY by 1.3%. Little did anyone know it at the time, but this negative print marked the beginning of a prolonged period of Chinese producer price declines. As it spread to consumer prices, China was enveloped by deflation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Today we look at deflation in China. We look at the causes behind this persistent deflation, we look at whether—and how big—of a problem this really is for China’s economy. Then we’ll look at why the authorities would allow deflation to persist in a centrally planned economy like China, and finally we look at why—breaking from a core tenant of traditional economic orthodoxy—deflation might actually be a good thing for China’s long-term goals.

The Causes of Deflation

As we have previously written, economist stalwart Milton Friedman once said that inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods. Perhaps unsurprisingly then, Chinese deflation is the exact opposite: too few dollars (yuan) chasing too many goods.

Historically the Chinese central government response to any kind of slowdown has been infrastructure spending. It became so commonplace that our clients selling commodities into China came to rely on government infrastructure spending to support commodity prices.

In recent decades, China has built infrastructure and grown other industries at a speed that seems hard to comprehend:

- China launched its first high-speed rail line in 2008. By the end of 2024 it had approximately 48,000km of high-speed rail in operation. Just to put that in perspective, second place on the list is Spain with under 6,000km of high-speed rail in operation.

- Alongside its growing EV industry, Chinese auto exports have soared. From very small levels just a few years ago, in 2020 China exported roughly the same number of cars as the US at about a million units. And last year China was the largest auto exporter in the world at 5.7mm cars.

- Also coming from almost nowhere, China now produces about 78% of global solar panels. As recently as 2010 China’s utility scale solar capacity was about 1 GW (0.001 TW). By May of this year it was about 1.08 TW—over a thousand-fold increase. Again to put it in perspective, while capacity factors make actual electricity production somewhat misleading, the US has in total about 1.25TW of installed electric power capacity.

- As we all know, China is the largest coal miner in the world by far, mining over half the world’s coal. It is the largest steelmaker in the world, producing over half the world’s annual steel. And—surprise—the largest gold miner in the world isn’t a traditional major gold mining country like Russia or Australia or South Africa—it’s China.

We could go on, but the point is that the amount of manufacturing capacity and productive capacity in China is staggering and its significance is under-recognized.

All of that production either must be consumed domestically or be exported. China has been able to navigate tariffs fairly well, and despite significant US tariffs decimating Chinese exports to the US, Chinese exports remain up—and strongly—so far this year. As of August exports were up 4.4% YoY.

But the bigger problem so far has been domestic consumption. Following a long overdue housing bubble burst Chinese citizens have been hesitant to increase consumption. This is called the “wealth effect”—if people’s net worth is growing, they are more inclined to spend—and vice versa in the case of China. It’s the same phenomenon that is behind record high stock prices causing strong consumption in the US currently.

And domestic consumption wasn’t all that strong in China to begin with. China’s household savings rate is already relatively very high at about 30% vs around 4% in the US. Despite consumer prices (CPI) showing deflation (Figure 2), consumer spending really has not yet responded. China retail sales were up 3.4% in August, below the 3.9% expected and below the 3.7% increase in July.

Figure 2.

Why is the Government Allowing Deflation?

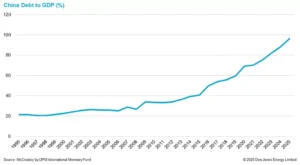

It’s not really a choice. The recent playbook of increasing infrastructure spending and stimulus in order to produce more goods would just result in even more oversupply and more deflation (along with more debt, Figure 3) if China can’t export all these goods or get more domestic demand.

Figure 3.

But could the government just give money to people to spend similar to the US post-Covid? Yes, the government absolutely could just print money and give it to citizens to spend. However, in 2024 China ran extremely high (compared to in the past) deficits of about 6.5% of GDP. While this is in line with the US deficit, it is much higher than most of the rest of the world. Even though China’s absolute debt level as a percent of GDP is far below that of the US’s of over 120%, if China is trying to position itself as a more fiscally responsible alternative to the US (which we think they are), running even higher deficits would be inadvisable.

Furthermore, just giving money to citizens probably wouldn’t have a very strong effect. American citizens only save around 4% of their income each year, meaning that money given to American citizens is almost entirely spent almost immediately and will stimulate the US economy. However, when your citizens have a savings rate of about 30%—like China the effect of giving cash away would be far more muted.

Related to this, we do not agree with fears that more government spending to support consumer spending would put downward pressure on the yuan. We think there are plenty of mechanisms available for a massive centrally planned economy to support its currency. We think that increased consumer spending would align well with a China wanting to be more fiscally secure on its own; a stronger consumer spending base means less exposure to the whims of foreign actors like tariffs. And as such we expect deficits much lower this year (closer to the 4% government target) and shrinking from here.

Is Deflation Even Always Bad?

We think deflation frankly gets a bad rap. In any sort of capitalist system, deflation is the default condition. As clever capitalists come up with faster, cheaper, and more efficient ways to create things, the cost of creating them ultimately falls. China becoming the inexpensive global factory of the world through innovations despite rising labor costs is a great example of this. The only reason we don’t see persistent deflation globally is because governments print money into existence and allow some—hopefully limited—inflation. There are a few reasons for this:

- (The theory that) Deflation reduces purchasing. In our Econ 101 classes we learned this was the biggest reason that deflation was bad. After all, if you were eyeing a new chair and knew it would be probably cheaper next year, why would you buy it now when you could save your money and buy it cheaper next year? The idea is that under deflation no one would buy anything and spending—and therefore the economy—would collapse. However, we just don’t agree with this premise. Take for example televisions, which along with laptops and other electronics are a good that generally sees price deflation. No doubt many of you paid a lot more for a TV years ago than a much bigger and better TV recently. Did you delay purchasing a TV, knowing that the price was going to come down? No. You may temporarily hold off a purchase for a sale but most evidence does not show consumers putting off purchases for longer periods of time for price declining goods.

- Deflation makes debt more expensive. Here is the real reason that deflation is bad: deflation makes debt more expensive. As the value of a dollar (or yuan) goes up from deflation, the value of debt denominated in those currencies goes up too. And in a system that is driven by debt, deflation would just be catastrophic. We have written extensively about debt issues in the US (see our Tariff Talk “Can the US outrun its debt?”), but inflation has chipped away at the real value of debt in the US by over 20% since 2020 alone simply thanks to inflation. Ultimately, a debt-based system not only can’t tolerate deflation, but really needs inflation.

Why Our Title: “Is China’s Deflation a Bug or a Feature”?

In the late 1800s the US saw a prolonged period of deflation. And it did a lot to shape the US middle class of the 20th century. With less of a formal banking system than today, deflation allowed US citizens to save money that was worth more later, actually building up a middle class in so doing. In this way, deflation might be China’s way of very slowly trying to build up its middle class at the expense of its producers.

China this week unveiled a variety of “mini stimulus” measures that did not require much money from the central government like pledging to open internet and culture sectors and encouraging the hosting of international sports, for example. All of these are designed to increase services consumption at little cost to the federal government.

Is deflation a concern for China? Sure – it increases the cost of debt. Does the rationale behind deflation make sense? Again, in our view, yes. It may mean lower margins for producers but ultimately deflation makes heavily savings-tilted consumers not only feel richer, but it effectively makes them richer. And this may ultimately make them start to spend. Were savings only 4% with massive record debts the effect of deflation would most likely be negative but with a populace with heavy savings? Deflation helps the consumer class. This is not an immediate result, but history shows that – as in the US example – it is a way to build up a middle class over time.

What Does This Mean to our Clients?

While we could be wrong (and have been wrong), our view is that stimulus from here going forward will not be as much on grand public works projects and supporting greater commodity consumption. Rather, we think the government focus will be on overcapacity and its resultant problems, like the over-exporting of Chinese goods into the international markets and the resultant antagonizing of important trading partners. That may be good news, for example, for buyers of steel from Brazil, or the sellers of metallurgical coal into Brazil.

Combined with that, the goal will be more domestic consumption. It is hard to push that overnight but if one wanted to increase domestic consumption, the moves now (including continuing to allow deflation) would be the way to do it. Deflation builds a middle class as wages tend to be more “sticky” and hold up while the cost of goods declines.

If China can get its citizens to unleash their savings into consumption rather than real estate, we think this can be a win/win for more or less everyone: less reliance on exports for foreigners, a higher standard of living for its citizens, and more taxes and revenue for local governments. It won’t be easy and we can’t say for sure it will work but against this backdrop allowing deflation to happen seems to makes sense. But for our clientele it would seem to cement something that we’ve been saying based on observation for a while: that the days of China have market-moving stimulus—with their resultant bump for commodities prices—appear limited.

By Charles Dayton, Associate Director, Research & Analysis, McCloskey